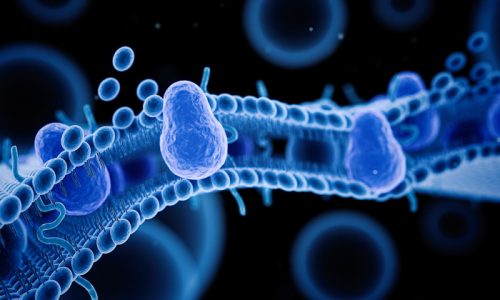

- Myelin is the protective coating around nerves in the brain and spinal cord that enables efficient signalling, but is damaged in MS

- A key goal of MS research is to repair damaged myelin and thereby restore nerve function

- New research funded by MS Research Australia has identified a gene that regulates myelin repair in a laboratory model of MS

Over the last two decades, research has delivered effective therapies to shut down the immune attack on the brain and spinal cord in multiple sclerosis (MS), reducing MS relapses. The new “holy grail” for MS research is to repair the damaged nerves in the brain and spinal cord and restore nerve function. This requires a greater understanding of how myelin is replaced, or “remyelination”, after it is lost in MS. New research funded by MS Research Australia has shown that deletion of a specific gene in the brain speeds up myelin repair in a laboratory model of MS.

What controls myelin repair in the brain?

In MS, the immune system mistakenly attacks and damages the myelin sheath around nerves in the brain and spinal cord. In the initial stages, the body’s natural repair processes drive remyelination and repair of the nerves. Over time however, this process cannot compensate adequately, and the resulting deficits in nerve conduction cause persistent neurological symptoms in MS. The myelin sheath is produced by specialised cells in the brain known as oligodendrocytes. In new research funded by MS Research Australia, Associate Professor Kaylene Young’s laboratory examined how a specific gene affects oligodendrocytes when myelin is damaged.

Switching off a gene improves myelination in an MS model

Using a laboratory model of MS, the team “switched off” this gene specifically in precursors of oligodendrocytes. This caused oligodendrocytes to mature faster, resulting in better myelin coverage of the brain after disease onset. In the non-MS brain, switching off the gene had a different effect. Rather than affecting maturation, more new oligodendrocytes were produced. This illustrates that myelin producing cells are regulated differently in the brain in response to an MS-like disease.

Overall, the team has shown that this gene, called LRP1, suppresses remyelination in a model of MS and have shown different effects of LRP1 in the non-MS brain versus the MS brain. Their work was published in the prestigious journal Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology and uncovers another potential process in the complex regulation of myelin repair. It is hoped that a greater understanding of this process will ultimately enable development of new therapeutic strategies to enhance remyelination.

How is MS Research Australia working to accelerate therapies for myelin repair?

For the last three years, MS Research Australia with the Macquarie Group Foundation has funded Associate Professor Young’s “Paired Fellowship” to work on remyelination in the brain. The Paired Fellowship funds a laboratory scientist and a clinical researcher (in this case, neurologist Professor Bruce Taylor, also from the Menzies Institute for Medical Research) to collaborate on a shared research program to translate research findings into new treatments.

Applications are opening soon for the next Paired Fellowship to fund discoveries translating to new treatments for MS. Also opening soon is MS Research Australia’s new targeted call for research into protecting and repairing the brain in MS, including a focus on myelin repair. Finally, MS Research Australia is investing in international research into myelin repair for progressive MS, as a managing member of the International Progressive MS Alliance.

It is our great hope that these initiatives accelerate the path to effective therapies promoting remyelination and repair for MS.